Milder TBI Disability Puzzle: Elizabeth Part Ten

We began the Elizabeth story with the quandary as to how she could wind up with so much more disability from a concussion and milder TBI than she had from an earlier brain injury involving coma and brain surgery. There is never a clear answer to such questions in any given case. Diagnosing brain damage requires us to look through the skull, tissue and within an organ with fairly crude measuring tools. What we get in a severe brain injury is usually a clear picture, because blood in the wrong place is easy to image on a CT scan and the processes that involve increases in intracranial pressure often involve pushing brain structures out of alignment. But just because a severe brain injury involves potentially life threatening damage if left untreated, does not mean that injuries to the parts of the brain that can occur in a concussion, do not have the potential to leave devastating long term disability.

The key to understanding Elizabeth’s disability is first to understand that Elizabeth’s brain was left highly vulnerable after her coma injury. While she had a remarkably fast recovery, the overall efficiency of her brain was drastically reduced. The extent of her recovery no doubt had to do with what is called plasticity, a phenomenon common in severe focal brain injury, such as she had. As a result of plasticity, the functions, which were done pre-injury by the structures in the brain that were damaged, are taken over by different structures. While neuronal tissue has great potential to be used interchangeably, the negative effect is that it significantly slows down the efficiency of the brain when such occurs.

For an analogy, picture what would happens to your day to day errand running if all the stores, gas stations and service businesses in your neighborhood were to suddenly close. While other businesses in other neighborhoods could still take care of most of your needs, you would have to drive greater distances and have to reacquaint yourself with the people and companies providing those services. Your whole life would work less efficiently but over time, your life- like the brain, would adapt, be “plastic.” In such analogy, the road system, the method of transportation is still working efficiently, it is just that the structure of accessing services has changed.

In contrast to the type of focal structural injury that Elizabeth had, concussion and milder TBI most often involves acceleration/deceleration forces that disrupt the brain’s communication apparatus – the brain’s circuitry, the axons. The axons are the long thin extensions of neurons that allow all brain cells to communicate with each other, the brain’s wiring system. The injury occurs not because blood vessels in a particular part of the brain are damaged by the impact forces, but because the long protrusions of axons are stretched and torn when rotational forces twist the brain’s core.

Concussions and milder TBI typically do not involve long periods of loss of consciousness, because axonal injury (diffuse axonal injury) may not involve the immediate catastrophic attack to the parts of the brain that control consciousness. Axonal injury actually involves a cascade of pathology where the cells continue to die for up to 72 hours.

Now if we use the analogy we started with assuming Elizabeth’s brain was like the neighborhood where all of the stores were suddenly closed, we must add to that confusion, a disruption in the road system to get around the community. While the stores are still open on the other side of town, half the roads are torn up and worse yet, a bridge is out. Now instead of quickly adapting to having to go the long way around, there are traffic tie-ups at each turn, and times of day when you just can’t get through. Had the road system problem occurred when all of the neighborhood stores were still open, the problem might have been minor, since no great distances would have had to have been travelled.

Elizabeth’s quandary is likely explained by this synergistic combination of structural changes to where services are performed in her brain by her first injury and the major disruption in the communication network of her brain in the second. The combination leaves her almost completely stalled, especially when high neuronal demands are placed on her brain. In other words, look out for rush hour. For her and other TBI survivors, rush hour in the brain occurs when too many attentional demands are made upon her, particularly as a result of stress, crowds, noises, pain or any other irritant to her cerebral cortex.

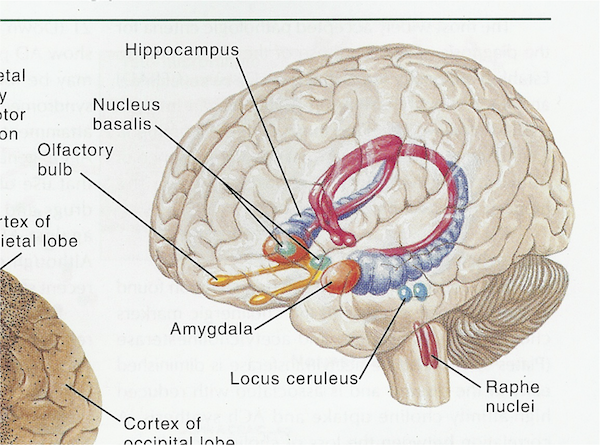

One final point in closing. Two brain structures and the way in which they communicate with the frontal lobes are undoubtedly part of her picture, based upon the significant functional changes in her memory and the issues she has with stress and anxiety. The structures are the hippocampus and the amygdala. Both are buried deep inside the brain, in an area called the limbic system. For a general treatment of brain anatomy, click here.

The hippocampus plays a huge role in short-term memory and the amygdala controls our most primitive emotional responses -including panic and anxiety. Amygdala involvement can alter the hippocampus function by putting an emotional priority onto certain memories.

These two structures are connected to the lower frontal lobes by an axonal fiber tract called the uncinate fasciculus. While Elizabeth’s hippocampus and amygdala were likely damaged in her first injury, the uncinate fasciculus damage might have been greater in the second. The uncinate fasciculus is a fiber tract of axons, very vulnerable to injury in the twisting of brain tissue seen with concussion.

In our belief, it is when the uncinate fasciculus’s capacity to efficiently transmit signals between the lower frontal lobes and the limbic system (the hippocampus and the amygdala) is disrupted that anxiety increases. Uncinate fasciculus damage can turn an anxiety disorder into a panic disorder. When anxiety increases, memory function plummets.

Diagnosing damage to the uncinate fasciculus requires a clinical judgment by the doctor, not some scan or other electronic gadget. While we hope that the MRI technique of DTI will soon be studying this tract more closely, there is a paltry of research on it to date. But some things, which are infinitely difficult to image in medicine, are easy to understand when you hear the stories of the survivors. As Elizabeth says: “The only thing I’m snapping with lately is stress, nerves, fear.”

That one sentence points us towards the uncinate fasciculus role in communicating the way fear, anxiety and memory are processed in the frontal lobes.